EGO - Errr Go On !

This post stems from my own experiences of a ten day Vipassana meditation retreat and explores different meanings of the word "ego", the relevance of these concepts, and includes neuroscience perspectives on ancient and modern usage of the word Ego.

PERSONAL STORIESHEALTHSCIENCE

Chris Russell-Jones

6/7/202518 min read

I recently returned from a ten day Vipassana meditation retreat : a non-religious retreat that teaches the meditation taught by the Buddha, however it isn't Buddhist; it is open to all adults (subject to health checks) and does not seem to require any commitment other than following the instructions of the practice as best as possible whilst on the retreat. I stayed for six days before leaving, the main reason for leaving was around mental confusion of some terms being used, especially "egolessness". The protective part of my brain was asking and then shouting, "why are you trying to turn me off, I'm here to protect you!".

Combined with the incredible intensity of the meditations themselves, and the lack of resource for researching the confusing terms (i.e. no talking, limited access to teachers, no phone or internet), I felt best to leave, regather and regroup myself, and reapply for the course once better prepared.

The meditations themselves were very real, very much based in my own experiences of my body and of insights, so the importance of what I was experiencing and understanding what was happening became really important; I came home and researched the terms I found confusing; in addition to "egolessness", also what is meant in this tradition by "training the mind"; what is the difference between "cravings" and simply having preferences and choosing accordingly; similarly for the understanding around "passion".

After doing some research at home, my queries were quite easily answered, and I learned loads about the mind and science along the way, this article is about the EGO! I have also noticed, and share below, how the word "ego" is used to mean so many different things by different people / traditions, which contributed to my confusion.

"Ego": the Basics

The etymology of "ego" traces back to the Latin word "ego," meaning "I".

In ancient philosophy (e.g. Descartes’ “Cogito, ergo sum” — “I think, therefore I am”), “ego” is just the thinking subject. But it wasn’t loaded with the emotional or psychological meanings it would later acquire.

Given there are lots of things that make up the "I" (or "me"), it is a very broad term! I could think of all my past experiences, recent experiences, genetics, environmental factors - all of these things and many more will influence my experience right now, how I am feeling, what I am thinking. It seems lots of different people have used this very broad word in their own tradition, as explored below.

It was Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) who first popularised “ego” in a psychological framework, though the original word he used was “das Ich” — German for “the I.” Freud originally wrote in German, using das Ich (the I), which was translated into English as ego. That’s when “ego” entered popular consciousness in its Freudian sense — as the rational self balancing instinct and morality. From this, Freud’s model is the origin of the psychological term “ego” as it’s widely used in the West.

In the West, the idea of the ego as a false self, or as the source of suffering, became popular much later — mostly from the 1960s onward, when:

Buddhist teachings (like Vipassana and Zen) became more accessible

Hindu Vedanta and yogic psychology entered popular awareness

Writers like Alan Watts, Ram Dass, and Eckhart Tolle reframed the ego as something to be transcended rather than managed

Interestingly, classical Eastern texts didn't use the word "ego" — they used Sanskrit terms like:

Ahamkara (“I-maker”) – the psychological function that constructs identity

Asmita – a kind of self-importance or egoic pride

But when these teachings were translated into English, the word “ego” was often used as a stand-in — especially in teachings about liberation from self-clinging.

"Ego" in Vipassana Tradition

From my own research (and very limited experience), within the Vipassana tradition, there are two types of ego:

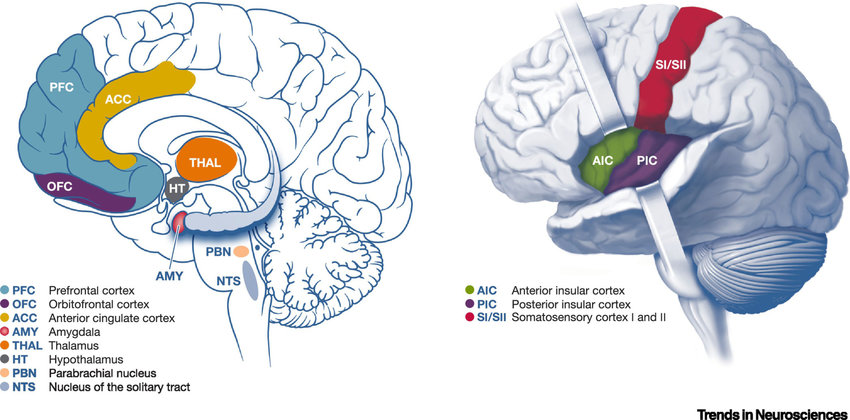

1. Ego & the The Limbic System

The limbic system, especially the amygdala (emotions centre of the brain) and how it communicates with the hypothalamus (the control centre of the brain, that controls stress response, adrenaline etc). These parts of the brain contribute to our fight or flight response : the amygdala detects a perceived threat, it responds and tells the hypothalamus to get ready to fight or flight. This can lead to us REACTING to a situation, without conscious thought or decision making. When we talk about people being reactive, e.g. someone spills their coffee in the morning and they lose their shit, perhaps shouting or swearing for example, this part of the brain is driving that: it is reacting to a perceived danger and triggering an engrained fear-based response.

It also arises in other situations e.g. in relationships, if in a disagreement with someone, we can become reactive, -perhaps reacting in ways that relate to to childhood experiences - our brains are in a rut of reacting in a certain way.

This is why so many modern day mental health approaches will encourage people to PAUSE as first thing - to take a break from the usual reactive pattern, to let that instinctual reactive impulse to pass, and then hopefully reflecting on how you choose to respond to the situation. RESPOND rather than REACT.

This RESPONSE process takes place in the brain in particular from the prefrontal cortex of the brain which is associated with attention, regulation and decision making. I.e. we are re-training ourselves to avoid reacting (associated with the amygdala and hypothalamus), instead making conscious decisions about how to respond (associated with prefrontal cortex).

All of these things can be and have been measured scientifically, e.g. with functionalMRI, Structural MRI (sMRI), EEG (Electroencephalography), MEG (Magnetoencephalography), PET Scans (Positron Emission Tomography) for one example of many click here .

The vipassana training retrains the mind so it gets out of the rut of reacting - perhaps the prime way it does this is Body scanning: the vipassana meditation involves scanning the body from a strictly observational and equanimity perspective - whether you are noticing pain or pleasure in any part of the body, it is to simply notice it, without changing the breath, without freaking out because of pain, without getting all excited because of pleasure - just to notice.

Our reactive responses to both pain (aversion, try to avoid/distract) and pleasure (craving, wanting more of it, feeling excited) are both in the amygdala / hypothalamus parts of the brain i.e. really evolutionary old and engrained reactive patterns of the human brain. The vipassana mediation technique is again and again training the person to simply notice.

For example, with pain, just an awareness of it, even go into it to notice it fully, you may even find the pain is less painful because sometimes the pain is actually our mental fear around that fact we think there is a pain; the pain itself may be ok / far less than we thought / even disappear in time.

With pleasure, the pathway is different: the sensation of pleasure itself (e.g. bliss, tingling, warmth etc) is simply that, the experience. However the attachment / craving / grasping / clinging to the pleasure creates an anticipation loop - it is the anticipation of pleasure that leads to a separate brain dopamine process : the mesolimbic dopamine system is triggered, especially via the ventral tegmental area → nucleus accumbens → prefrontal cortex. The focus on getting the pleasurable sensation again triggers this limbic reaction (ancient part of brain, see section below).

Like the fight-or-flight system, this mesolimbic system runs on speed, simplicity, and emotional charge — not nuance or contemplation. So to be clear, mental craving activates dopamine.

Dopamine acts as a neurotransmitter in the brain, leading to motivation, focus, and goal-directed behaviour — it’s what gives experiences their “pull”, and it’s closely linked to addiction and reward-seeking.

Dopamine also functions as a hormone in the bloodstream, where it regulates the body’s systems — supporting things like blood flow, hormone balance, and kidney function — to keep the body stable and responsive while the brain is pursuing something it wants.

So in this way:

Craving something (a dopamine loop) and

Fearing something (a fight-or-flight loop involving adrenaline, plus cortisol to sustain energy when the threat response is prolonged)

…are two sides of the same ancient limbic coin: systems designed to grab your attention and and drive immediate action, whether toward pleasure or away from threat.

In my own very early / initial experiences of vipassana meditation, it clearly helps me start to notice my body's physical reaction to pain or pleasure , and it seems completely achievable and beneficial to retrain myself to avoid falling into 'limbic' response patterns, instead to remain equanimous and to observe the sensations rather than pull away or dive into them i.e. rather than react to them.

Interestingly, I notice that when simply observing, this seems to be related to experiencing insights about myself, seems to be where / how vipassana meditation can feel like lifetimes of therapy - insights about myself may just appear in my mind; I suspect there are links with e.g. The body keeps the score by Bessel van der Kolk, or the work of Gabor Mate - our body stores stories and memories and by noticing sensations in our body, we also notice memories. E.g. if we experience a sensation in our body, and really pay attention to it, we are actually paying attention to some information in our body (e.g. a memory) which is present.

Through vipassana meditation, people become aware of more and more subtle sensations, which can relate to more and more subtle memories that have been stored, i.e. uncovering the many layers that make up who we are.

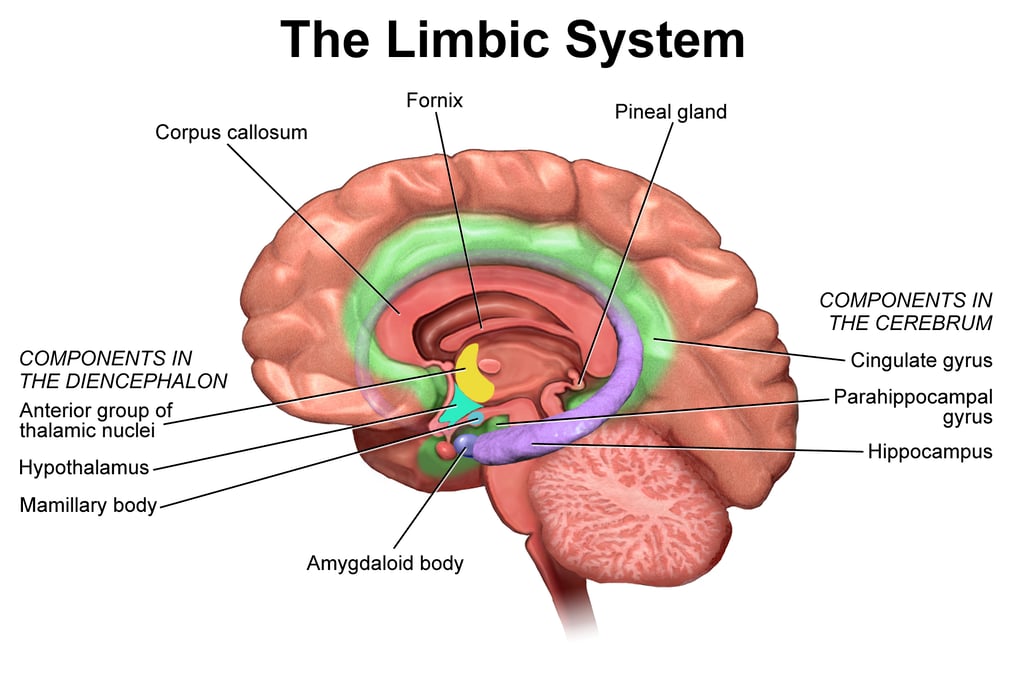

Science of The Limbic System

The limbic system : "limbic" comes from Latin for "limbus", meaning border / edge, referring to the parts of the brain that form a border / ring around the brainstem and inner part of the cerebral cortex . It is sometimes referred to as the "emotional brain", it is evolutionary older than the neocortex, meaning its deeply linked to survival instinct and emotional life long before complex reasoning evolved. It's not a single structure, but a network of interconnected areas, including:

Amygdala – processes emotions like fear and anger

Hippocampus – involved in memory and learning

Hypothalamus – regulates autonomic and endocrine functions

Cingulate gyrus – emotion formation and processing

Thalamus (parts) – relays sensory information

Olfactory bulb – closely linked with smell and memory

By BruceBlaus. When using this image in external sources it can be cited as:Blausen.com staff (2014). "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. - Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31118604

In psychology, particularly in Freudian thought, "ego" refers to the conscious aspect of the psyche that mediates between the id (primitive desires) and the superego (moral conscience). In everyday language, "ego" often refers to a person's sense of self-importance or self-esteem.

2. Ego and the DMN Response (Default Mode Network)

The Vipassana tradition also looks at ego in a second way: as the story / idea / construct we hold of who we are, typically based on stories from the past, perhaps from childhood, through which we construct this idea of who we are, our sense of identity, which we then project outwards into the world.

This is typically constructed from the resistive stories which run through our mind, often worries about our life, and whilst based in the past, they are often also based in the future - our anxieties about what may happen in the future, affecting our sense of identity right now. In the future I may get this hereditary disease , influencing how we feel about ourselves and life in the present, and about our identity.

In everyday language, when we say, "he has a big ego", we are often mean they’re projecting a self-image of importance - maybe to cover an inner sense of lack which may stem from childhood. If it's really obvious, people may notice it and comment on it. In reality, I suspect we ALL have (or have had) "really big egos" , just not necessarily projected in such an obvious way to the world.

Returning to the Vipassana tradition, the problem with this type of "DMN Ego" (see below for DMN) is that it limits us in life. If we live by the stories of our past, then we will ALWAYS be the person who doesn't feel good enough, or who fears the future etc - we will ALWAYS be stuck in the same misery of our past or future. So if we want to change our experience of life and be free of this misery, we must address our brain's tendency to repeat these stories of past and future, and simply bring ourselves into the present.

Within vipassana meditation , this is done by the same meditation mentioned above: being aware of the sensations in the body e.g. in the nostrils as the breath enters and exits. The mind WILL wonder off, and after a while, I can attest to this personally, you may notice, either the mind wanders to stories from the past, or the mind wonders into stories of the future. They may be dreadful stories, or wonderful stories and really enjoyable way to spend another 20 minutes out of the ten hours of meditating you are doing that day! The training though is to notice, yes my mind has wandered, and now I am choosing to bring it back to the present sensations in the body. There's nothing wrong per se in thinking about the past or future, wonderful and important things - however if unchecked, we live by the stories our DMN-mind creates, and we are trapped in those stories.

By training oneself to be able to notice the wondering mind, and return to the present moment, it becomes possible in life in general to stop being defined by those stories, and to make different choices. E.g. to simply notice how you are feeling right now in the present; or to say, hey, I'm having really negative thoughts about the future right now, I choose to think about other options for my future and to have different beliefs about my future.

Default Mode Network (DMN)

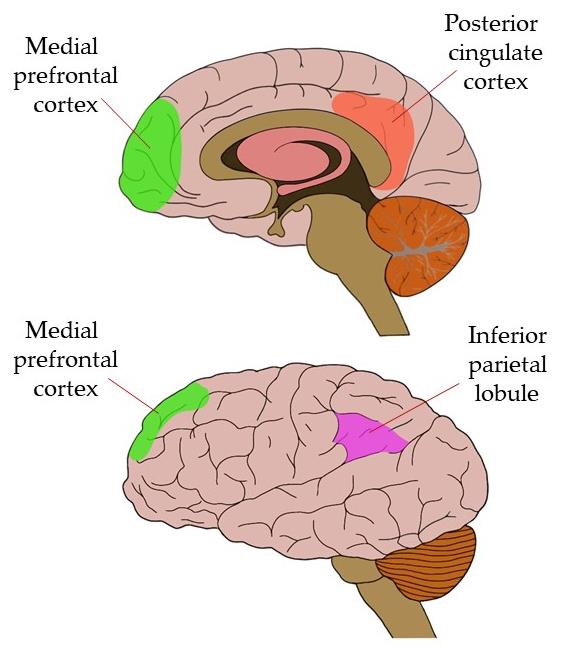

The DMN is a network of brain regions active when the mind is at rest and not focused on the external world. It includes:

Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) – "me-centered" thinking

Posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) – evaluative thoughts, autobiographical memory

Inferior parietal lobule – integrates sensory info with self-image

Hippocampus – memory formation (especially around “my story”)

It supports self-referential thought, daydreaming, and rumination. Overactivity in the DMN is linked to anxiety, depression, and a strong narrative sense of ego. Mindfulness practices reduce DMN activity, leading to less identification with thoughts and a more present-centered awareness.

The Default Mode Network

https://neuroscientificallychallenged.com/posts/know-your-brain-default-mode-network

Science tells us that these parts of the brain are activated when daydreaming, ruminating, at rest.

Some parts of the DMN are ancient, such as the hippocampus. Other parts, notably the prefrontal cortex, are the most recent on evolutionary perspective, and whilst shared with other primates, it is uniquely expanded in humans, and support complex thought, autobiographical memory, social comparison, and future planning - i.e. it supports higher-order human thinking, benefitting humans providing us with the ability to :

Reflect on ourselves (“What kind of person am I?”)

Rehearse future scenarios (“What will happen if…?”)

Build and maintain social bonds (“What do they think of me?”)

Integrate memory into identity (“Because this happened, I became…”)

As mentioned above, a downside is that these same gifts can trap us in suffering — via rumination, anxiety, shame, and repetitive identity stories. Vipassana and mindfulness address this by developing our ability to come out of those stories and come back to the present moment.

Conscious Awareness Itself

So who is this "I" that chooses to escape the limbic reactive way of thinking, that chooses to escape the DMN closed-story way of thinking? Where abouts in the brain does this conscious awareness self reside?

This is one of the most mysterious and debated areas in cognitive science and contemplative neuroscience; based on current understanding:

When you're in the present moment — not lost in fear, not lost in story — the brain shifts from DMN/lower limbic activity to prefrontal, cingulate, and insular networks:

Anterior insular cortex — sensing the internal bodily state (interoception)

Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) — tracking attention, catching mind-wandering

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC). — regulating emotion, sustaining focus (toward the top of the prefrontal cortex, on the upper sides of the frontal lobes, roughly around your temples and top forehead)

Somatosensory cortex — noticing sensation in specific body parts

Thalamus — sensory relay gate, coordinating input (just above the hypothalamus)

[And importantly: Decreased activity in the Default Mode Network, especially the medial prefrontal and posterior cingulate areas (those involved in narrative self and time travel).]

So the "chooser" — the part of you that says, “I am aware I’ve wandered off” and redirects you to the now — is a functional network rooted in the prefrontal cortex and insula, with support from attention-monitoring circuits - as per list above, see also diagram below showing the different parts of the brain activated in this process. Awareness appears to be a network phenomenon, not a single "spot."

In terms of evolutionary age: The oldest parts (like the thalamus 500 million years old and insula 300 million years old) support raw sensory awareness and interoception. The newer parts (like the dlPFC 50 millions years old and ACC 200 million years old) enable reflective self-awareness, conscious choice, and meta-cognition — uniquely human capacities. So, awareness as felt presence is ancient, but awareness as conscious observing ego or meta-awareness is a relatively recent evolutionary development.

To summarise, per current scientific understanding, there is no known "seat" of the self in the brain — the "I" that notices is not a single region but an emergent process, likely involving fronto-parietal networks that coordinate attention and working memory.

Vipassana would say: “The noticer isn’t the ego — it’s awareness itself. It doesn’t live in a structure; it watches structures arise and fall.”

Who is the Noticer?

Each of us has our own views on who is the noticer. In terms of modern scientific evidence on it, clinical near-death experiences can shed interesting light on the matter, e.g. on the question, does the noticer exist independent of the brain / body, or is it part of it. Or put another way, is the brain / body a temporary home of consciousness, or is consciousness solely a part of the brain / body.

There are well-documented cases of people who were clinically dead (no heartbeat, flat EEG or no brainwave activity); then revived, and reported lucid experiences, sometimes including:

Floating above their body

Seeing medical procedures they shouldn't have been able to perceive

Hearing conversations, describing instruments or actions in detail

One well-known study into this area is The AWARE Study (2014, Dr. Sam Parnia, University of Southampton) which studied over 2,000 cardiac arrest survivors with. One patient, for example, recorded accurate visual recall of events during a 3-minute period when there was no detectable brain activity. He described specific medical tools and staff behaviour from a visual vantage point above his body; this is one case case often cited as hard to explain by "brain-only" models. See also 2014 PubMed article on the above, and a separate 2023 PubMed article on consciousness and awareness during carding arrest.

Another area I find provides interesting insights into the existence of consciousness separate from the brain / body is studies on evidence for reincarnation e.g. young children who have very exact memories of their previous lives which are documented and examined, see for example the 1966 book Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation by North American psychiatrist Ian Stevenson MD.

Notes :

The AWARE study and Ian Stevenson’s reincarnation research disclaimer: These are contested areas in mainstream neuroscience.

Interoception is the internal sensory system that provides awareness of the body's internal states and signals. It's the "eighth sense" that helps us understand how we feel, whether we're hungry, thirsty, or experiencing other internal sensations. Interoception allows us to connect with and identify what's happening within our body, answering the question "How do I feel?"

"Ego" in other traditions

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud,the well-known psychoanalyst of the early 20th century, also used the word "Ego", although differently to what is discussed above. He used it in combination with the Id and the Superego. Freud’s theory wasn’t based on brain scans — but modern neuroscience has drawn loose correlations between these concepts and brain regions

ID: Linked to the limbic system (especially the amygdala and hypothalamus), the id represents drives, emotions, impulses, fear, hunger, and sex. It is present from birth and rooted in our animal nature.

SUPEREGO: Associated with the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and insula, the superego reflects moral reasoning, guilt, empathy, and social judgment. It emerges through socialisation, as we learn ideas of “right” and “wrong.”

EGO: Mapped to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), the ego is responsible for executive functioning, planning, inhibition, and regulation. In Freud’s model, the ego negotiates between the demands of the id and the constraints of the superego. It’s the part of the psyche where conscious awareness primarily resides, and its role is not about being boastful or egotistical — rather, it’s about managing internal balance and making practical, reality-based decisions. In short: Freud’s ego is the conscious regulator that helps us make reasoned choices between instinct and morality.

We can for example see that Freud's use of the word Ego relates to different part of the brain (dpPFC) compared to the Vipassana approach, which can be confusing! Freud's approach is more looking at being free of the ID (childhood influences) and SUPEREGO (social influences) - both major factors presumably for Freud's clients - and using the EGO to have more choice in life.

Carl Jung

Similar to Freud, the Ego is not the 'enemy'. Jung uses the term to refer to the "centre of consciousness", the self-awareness - in the sections above, what I refer to as the conscious awareness.

The ego plays a key role in navigating both the outer world and the inner landscape — especially in relation to what Jung calls the unconscious, which includes both the personal unconscious (repressed memories, forgotten experiences) and the collective unconscious (shared human archetypes). Jung refers to “the Self” as the totality of the psyche — a larger, more complete identity that includes both the conscious ego and the unconscious.

In today’s neuroscientific language, Jung’s ego may loosely correspond to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) — the part of the brain involved in executive function, regulation, and self-reflection.

His concept of the Shadow (the rejected or hidden parts of the personality) could be associated with limbic system activity — emotional memory, instinctual reaction, and affective charge. Meanwhile, his ideas around Archetypes and the Self might map onto dynamics of the Default Mode Network (DMN) — the system involved in identity construction, narrative thinking, and introspective states.

Jung’s approach to psychological and spiritual development — known as individuation — is the lifelong journey of integrating the unconscious into conscious awareness in order to become whole.

Cognitive Psychology / Neuroscience

In cognitive psychology and neuroscience, the term “ego” is rarely used explicitly — it’s largely a term from psychoanalytic theory. However, the functions historically associated with Freud’s or Jung’s ego are studied in great detail under more precise terms like executive function, self-regulation, cognitive control, and self-referential processing.

From my own understanding of the above, one could summarise by brain region:

Limbic system:

Vipassana: Considered the reactive mind — home to craving and aversion, seen as a major component of egoic suffering.

Freud: Identified as the Id — the source of instinctual drives, such as sex, aggression, and fear. It operates unconsciously and demands immediate satisfaction.

Default Mode Network (DMN):

Vipassana: The narrative self — the mind’s tendency to dwell on the past and future, generating identity-based stories and attachments. This is also part of what’s considered the ego in this tradition.

Freud: Not explicitly identified in Freud’s time, but modern scholars have suggested that DMN activity overlaps with ego-id conflicts, especially when ruminating or engaging in internal dialogue.

Prefrontal cortex:

Vipassana: Often associated with the observing self — the “noticer” or present-moment awareness. This is not considered part of the ego, but rather the capacity to witness thoughts and sensations without attachment.

Freud: This region aligns most closely with the Ego — the rational mediator that balances the needs of the id and the demands of the superego. It’s responsible for planning, inhibition, and reality-testing.

Death of the Ego

This is a term I have heard used in different situations over the years, and I wonder if it is useful to examine what it may mean in relation to the different concepts we have discussed above :

Freud: Freud never spoke about “ego death.” He saw the ego as essential for reality-testing, rational decision-making, and sanity. In Freudian terms, ego death might actually look like a psychotic break, where the boundary between internal fantasy and external reality dissolves.

Jung - Jung also didn’t promote ego death. He viewed the ego as the centre of consciousness, not something to destroy. His emphasis was on integration: bringing the ego into relationship with the unconscious and the greater Self. His lifelong project, individuation, was about the ego expanding and maturing, not dissolving.

Neuroscience / Cognitive Psychology: Neuroscience doesn’t refer to “ego death” because the ego isn’t a distinct brain part. But modern research into psychedelics and meditation has revealed something comparable: Default Mode Network (DMN) deactivation. The DMN, particularly the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), becomes less active during Deep meditation, and Psychedelic experiences (e.g. psilocybin, LSD, DMT). This network is usually active during:

Thinking about yourself

Replaying the past or imagining the future

Daydreaming, ruminating, and narrating experience

When the DMN quiets, people often report:

Less mental chatter

Less identification with their self-story

A sense of unity, spaciousness, or timeless presence

No boundary between self and world

These shifts can be profound, especially for people used to a dominant inner narrator and has been linked to reduced depression and anxiety for example - although also can be experienced as disorientating and terrifying (this article is not recommending use of psychedelics for example). This state of de-identification from the ego is often described as "ego death." However, the ego hasn’t actually died: narrative thoughts often return, and the limbic system still reacts. What changes is the relationship to those processes.

Vipassana: Like neuroscience, Vipassana doesn’t speak of ego death as destruction. Instead, it emphasizes disidentification from egoic processes — especially reactivity (limbic system) and mental stories (DMN). The practice is to observe these patterns without clinging or aversion, thereby loosening the ego’s grip on perception and behaviour.

In summary , none of the approaches seems to have a definition of death of the ego that actually means death. The closest seems to be from neuroscience / meditation / psychedelics around being less defined by the limbic reactive response and DMN network to experience a different sense of self. However, where the ego is defined as parts of the limbic and DMN network, then killing off those parts of the brain seem undesirable even if possible.

Conclusion

The word "Ego" in relation to our self identity within today's usage originated with Sigmund Freud, who saw it is a healthy vital part of our brain (which we could now say is loosely correlated with the prefrontal cortex). The word has been used in similar fashion (i.e. where the ego is a positive part of our brain) by other psychoanalysts such as Cark Jung.

The more negative concept of Ego, where one can try to train it so it doesn't overtake, comes from meditation traditions such as Vipassana, where they have adopted the western (Latin) word, however for very different interpretation of the word "Ego". Here, it could be described as about training the limbic and DMN network - which are goals it shares with Freud and Jung, just using the same words in different ways - confusing!

'Death of the ego' isn't promulgated by any of the approaches, certainly not Freud / Jung. The closest thing is changing relationship with limbic / DMN parts of our brains so they don't rule the roost, and some people find meditation, psychedelics, talking therapies may help in this regard.

This article has also touched upon:

The use of psychedelics on sense of self and links to studies on mental health,

If "I" am not the limbic or DMN part of my brain, then what am I - who is the noticer? the article has touched on some scientific research around near death experiences and evidence around reincarnation cases;

I may return to these topics in future posts!

Location

Online &

Cowbridge, South Wales

United Kingdom

Contacts

crjcoaching@gmail.com

COACHING * MINDFULNESS * MEDITATION

© 2025 All Rights Reserved